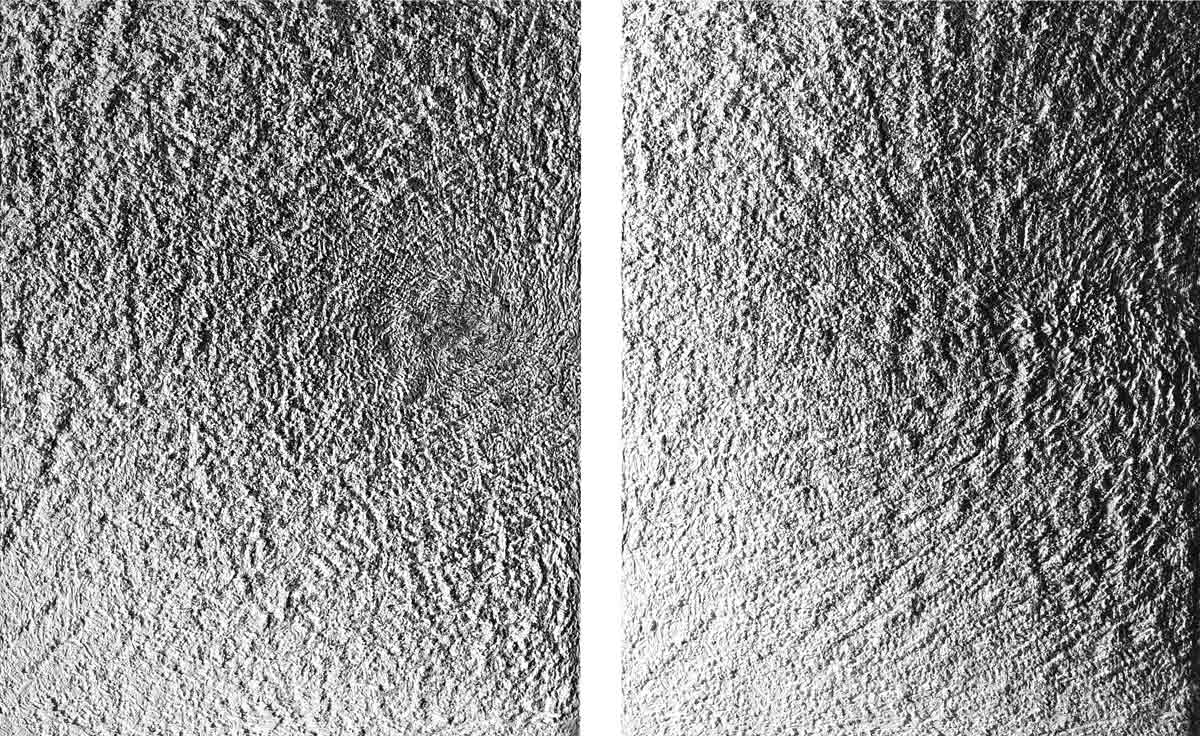

I. Kornputz

Kornputz ist weiss, grob und scharf, schafkantig. Viele Häuser sind damit verputzt.

An diesem Putz schürfte man sich als Kind beim Versteckenspielen die Ellbogen

auf, wenn man, um sich zu erlösen, scharf um die Ecke sauste. Mit seinen

Kornputz-Bildern spielt Andreas Greber ein Versteckspiel, und statt die Ellbogen aufzu-

schürfen, schärft er die Wahrnehmung: Mit Kornputz und Fotografie. Zuerst ist da

nur Kornputz, weiss, grob und scharfkantig, auf 16 Holzplatten geklatscht.

Sonst nichts. Wenn da nicht die Schatten wären. Die Schatten sind reine Fotografie.

II. Lichtbild

Andreas Greber begann mit der klassischen Reportagen- und Dokumentarfotografie.

Für die Monatszeitschrift du gestaltete er Beiträge über Glashäuser

in Botanischen Gärten und über vergängliche Momente auf Zugfahrten

durch Europa. Noch seine durch Koloration verfremdeten, erfolgreichen

Impressionen der Badeszene in Rimini und seine Ball-Bilder waren letztlich der

Dokumentarfotografie verpflichtet. Dann begann die Rückbesinnung auf das

Elementare der Fotografie, auf das Licht-Bild. Greber experimentierte: Das

fotografierte Auge projizierte er auf Gipsbüsten - Aug in Aug; dann die Schneiderbüsten,

die pygmalionähnlich, durch Fotografie lebensecht gemacht wurden - Akt

auf Akt; dann Materialexperimente, bei denen Bilder etwa auf verrostete

Metallplatten fixiert und damit zwei chemische Prozesse verbunden wurden -

Chemie zu Chemie. Alles geschah immer im Bestreben, die abbildhafte Enge der

Fotografie zu überwinden, im zeitgenössischen Bewusstsein, dass die Reflexion der

Gegenstände auf dem lichtempfindlichen Material über das Abbild hinaustreibt.

Greber trieb es fast gegenläufig - wie in den Schneiderbüstenakten - zu tendenziell

uneingeschränkter Identität von Gegenstand und Abbild. Erst wenn die

Übereinstimmung volkommen erreicht ist, bricht sie auf.

III. Bündelung

Der Fotogra bannte Schatten des Vergänglichen auf die Wände.

Es ist eine Art von Erinnerungsbild, mit dem er sich beschäftigt, so auch im Projekt

zum Beinhaus in Naters im Kanton Wallis, oder in der Eidgenössischen Finanzverwaltung in Bern, wo die Spuren einer Installation von tausenden von Dachlatten an die Wände

gebannt sind. Während die Dachlatten selbst als Objekt eine neue, äusserst

geordnete Form repräsentieren, erinnert die auf der Wand an das Chaos der Installation.

Die Spannung von fixiertem, aber chaotischem Bild - es misst über 80

Quadratmeter - und geordnetem Urmaterial macht die Qualität der einfachen,

technisch aufwändigen Arbeit aus. Und um diese scheinbar einfache Spannung von

realem Material oder Urbild und Bild oder Abbild kreisen die Arbeiten von Andreas

Greber. Keine Erkenntnistheorie seit Platon kam um diese Gedankengänge herum.

IV. Schatten

Aber Andreas Greber materialisierte mit den Mitteln der abbildhaften

Fotografie genau diese Spannung. Nichts ist wie es ist, erst recht ist nichts, wie es

gesehen, geschweige denn abgebildet wird. Lange dauerte es, bis diese

erkenntniskritische Einsicht auch für die Fotografie fruchtbar wurde. Greber führt

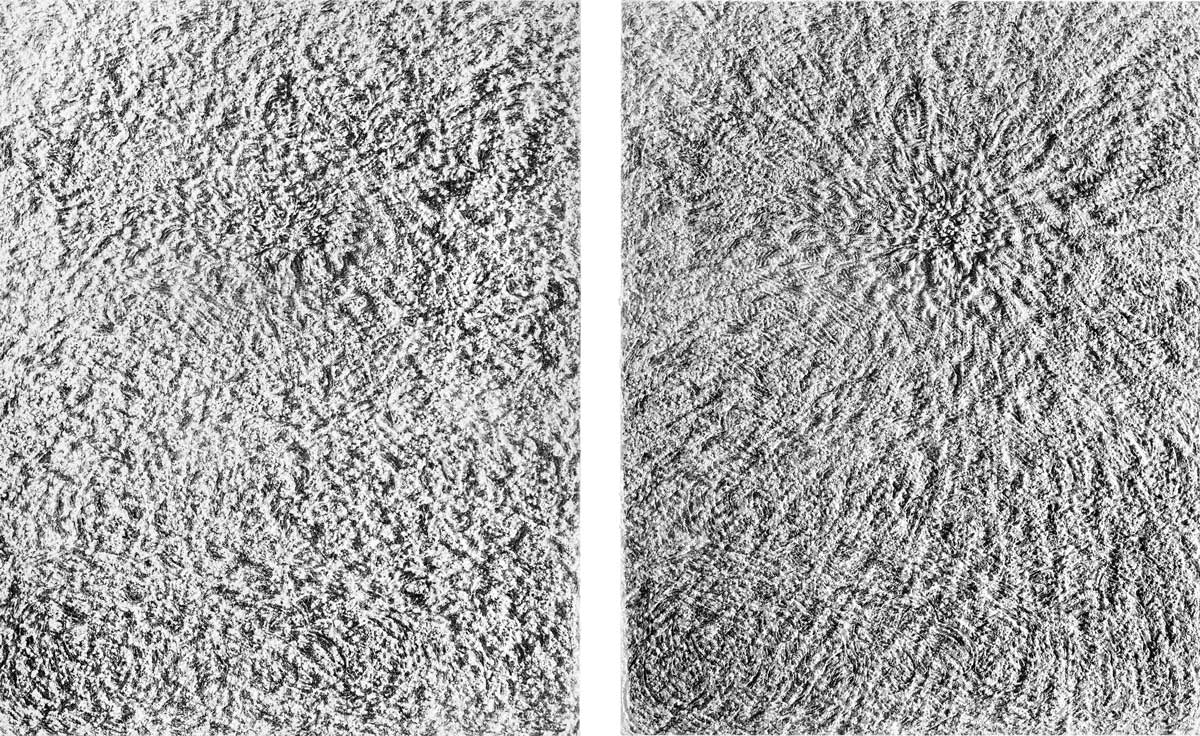

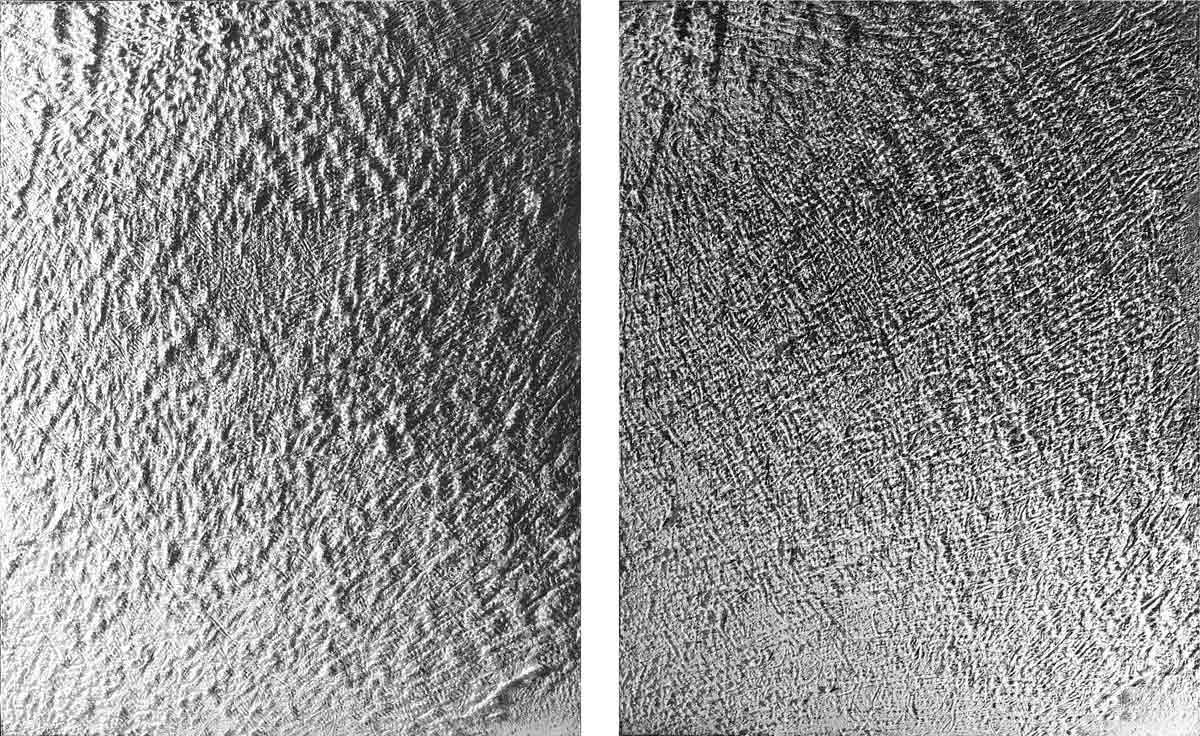

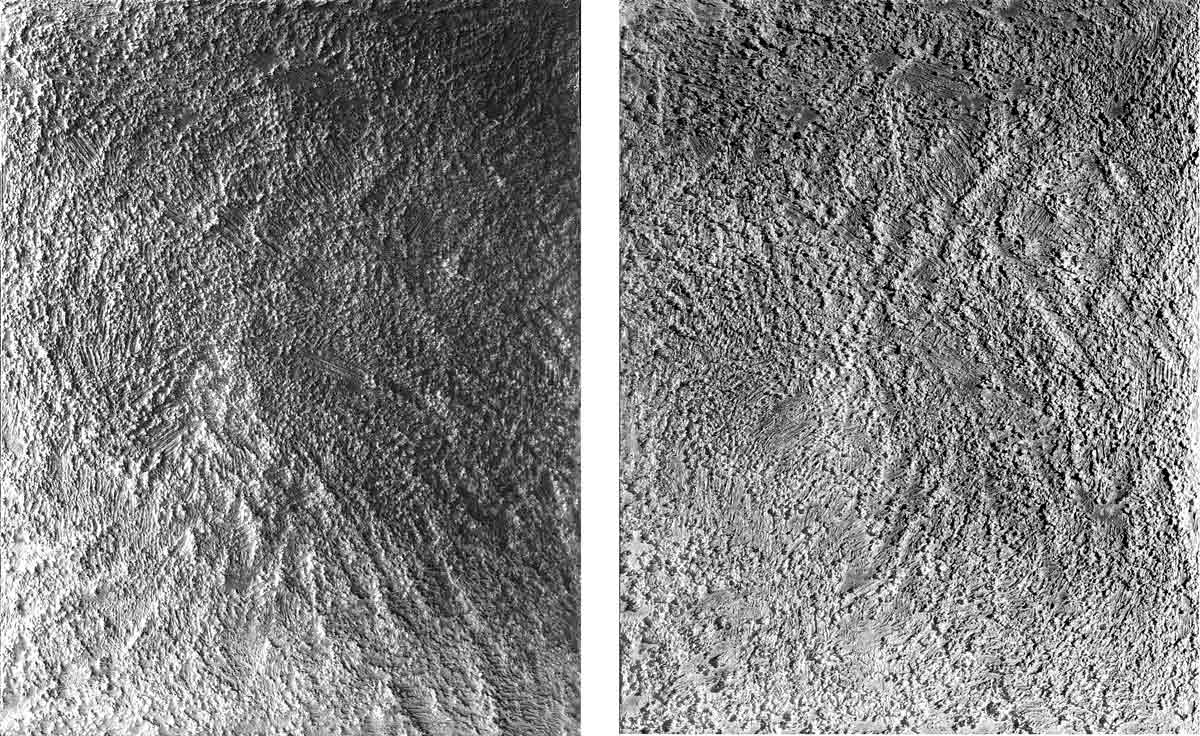

sie in seiner neusten Arbeit auf eine einfache Grundform: Hier ist der Kornputz auf

der Platte, die Platte wird fotografiert, die Materialfotografie wird auf die mit einer

lichtempfindlichen Beschichtung versehenen Platte

zurückprojiziert: künstliches Abbild auf künstlicher Wirklichkeit. Hängen die

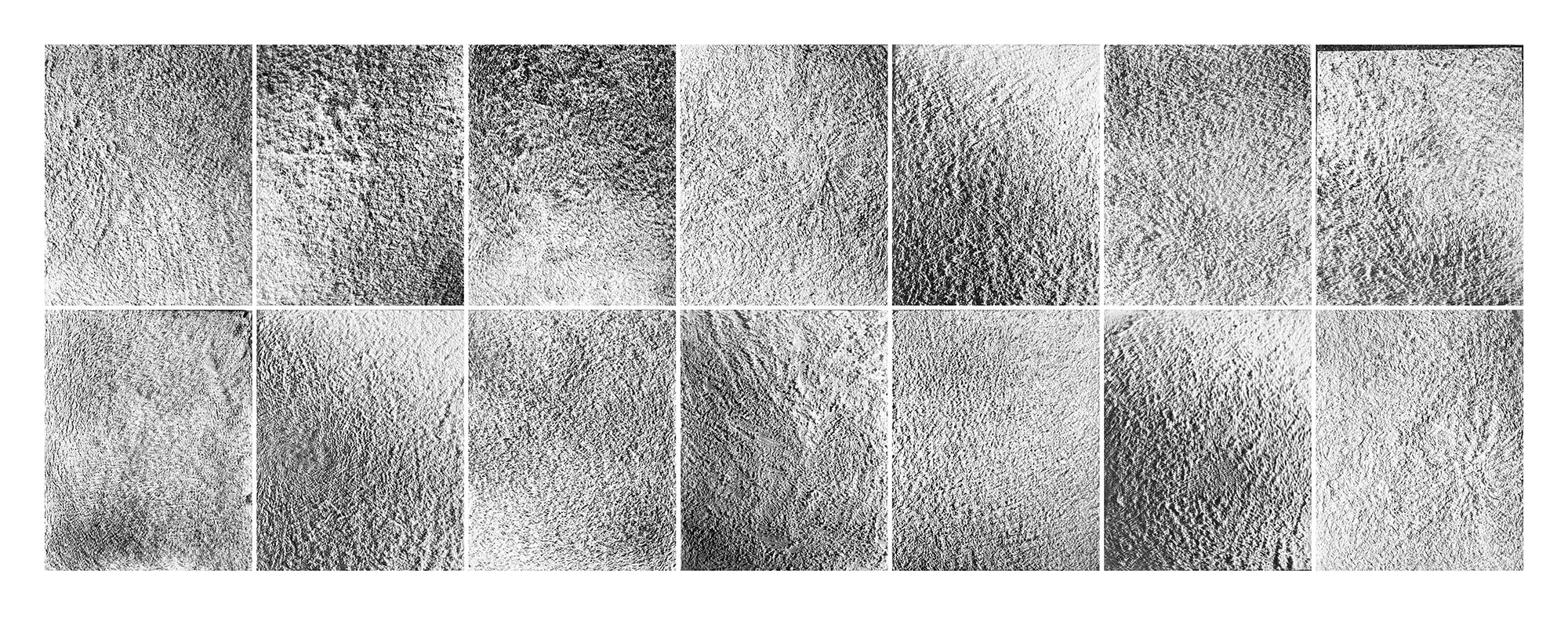

16 Platten nebeneinander, sieht man: keine gleicht der anderen. Der Bewurf bestimmt, wie der

angeworfene Kalkputz sich strukturiert. Die Fotografie fixiert das zufällige

Ergebnis. Das auf die Platte die zurückgeworfene Abbild ist jedoch nicht dem Zufall überlassen. Erst das Abbild macht die Platte mit dem hässlichen Kornputuzum Objekt, das in seiner Einfachheit auf die Anfänge der

Fotografie zurückverweist, ja geradezu vor die Fotografie zurückgeht oder die

Fotografie hintergeht, indem das Abbild als realer Schatten der Wirklichkeit

erscheint.

V. Simulation

Die 16 grundverschiedenen Platten mit dem hässlichen

Kornputz und seinem nie identischen Abbild scheinen im wechselnden Licht erst

die einfache Schönheit des wechselnden Lichts zu zeigen. Auf das Bild selbst als

Bild fällt dadurch ein Licht. Ins Licht grückt wird, was ein Bild zum Bild macht: seine Differenz oder seine verschobene Intentität. Die Reihe von Kornputz-Bildern wird damit zur einfachsten, ästhetisch herausfordernden Simulation der Simulation. Und was dabei das Merkwürdigste ist: Die Abbilder, die sich in der Differenz so sehr der Wirklichkeit nähern, lassen sich nicht abbilden. Diese Fotografie ist nicht weiter fotografierbar.

Konrad Tobler